Some thoughts from the internet on the future of theatre

Hipster dance classes are taking off in LA. Photo credit nytimes.com

by Michael Wheeler

The past week has hosted some novel conversations on contemporary theatre and how it is developing. Most interesting is how all of these perspectives are contributing to a larger conversation about what form theatre can take to engage, well, anyone under 40 who isn’t already in theatre. Here are some recent highlights:

In The Guardian, Lee Hall laments that the 20-30% arts funding cuts will bring down the curtain on British theatre’s golden age. At the core of his argument is that the new budgets will leave theatres unable to take artistic risks or be able to nurture and mentor the next generation of artistic talent:

“The post-1945 consensus understood this completely. The need for municipal theatres, the need to fund the experimenters (who of course become the next establishment), the need for national institutions, the need to represent the rich diversity of our society – allowing a place where we can all become richer by including the excluded – was centrally important to the interventions made. But more than this, there was an implicit understanding that our greatest talent could not be nurtured without support.”

Meanwhile on the other side of the Atlantic, Huffington Post critic Monica Westin has a decidedly more upbeat perspective on Why Hipsters Will Save Theater in her review of David Cromer’s Cherrywood. Her thesis proposes that the ironic disengagement that permeates hipster culture has the potential to create a new kind of theatre, that combines both “alienation effect” and “happening”. They (we), are capable of creating and enjoying this new approach to art as “the first generation of bohemian youth culture that’s not going to look like idiots–like the hippies and the punks–later for pretending to have all the answers, when all we had was a new way of dressing stupid.”

“But it’s the combination of the alienation effect and the happening that makes Cherrywood so important. In 1968 Peter Brook declared in The Empty Space that “The alienation effect and the happening effect are similar and opposite–the happening shock is there to smash through all the barriers set up by reason, alienation is to shock us into bringing the best of our reason into play… leading its audience to a juster understanding of the society in which it lived, and so to learning in what ways that society was capable of change.” How does alienation work? According to Brook is can use any rhetoric: “It aims continually at pricking the balloons of rhetorical playing–Chaplin’s contrasting sentimentality and calamity is alienation.” Brook couldn’t imagine a theater piece in which both could happen at once; life now demands this of theater, and Cherrywood delivers it.”

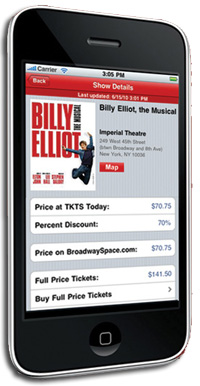

Of course you can’t be a theatre-conscious hipster looking for the latest, coolest, cheapest tickets you can find without this new Ap for your iPhone, which lists all the Broadway and Off Broadway shows and discount rates that TKTS has available each day. This sort of technology is probably much better suited to attract the new generation of potential theatregoers that make same-day plans and aren’t looking to fork out an arm and a leg for a night out on the town. Is there the potential for indie companies to collaborate through this same technology? Now that we have thrown out the notion that we have to perform in the same space to have marketing/ticketing alliances shouldn’t we be all over this?

If you used your iPhone to get tickets, maybe you should keep using it once the show starts? Over at 2amtheatre they had a multi-perspective post and conversation about the type of interactive, invite the audience to communicate with their PDA during the performance type of stuff Praxis was experimenting with in March at Harbourfront Centre. The consensus opinion seemed to be that imposing tweets on pre-existing scripts was a recipe for disaster, but that tweeting during shows had the potential to expand the medium if the pieces were built with this level of interactivity in mind. Travis Bedard provided some questions that should be considered while choosing to make work this way:

“But what can this technology enable for a playwright or deviser creating NEW work?

This is another possible tool on the utility belt for writers. It is indeed another entire plane of existence for characters.

Can extra-stage characters exist only in the Twitter-verse? Can the audience team up with one another for or against the stage characters?

What does the interaction between the sequestered, in-space audience and the free range Twitter audience look like?”

How well can the playwright and director control that?”

This last question is probably why there hasn’t been a HUGE amount of experimentation with this sort of thing. It is a process that confers less power to both playwright and director. Unproven methods that reduce the influence of the artistic leaders of a project are tough to get off the ground. I’m also a little confused about why Twitter is the only option being discussed as a technology to do this sort of thing. Facebook statuses, texts, tweets, IM, email, skype – we’re all using interactive digital technologies to improve our capacity to communicate. Why stratify it to a single tool exclusive to, well, hipsters? If we’re going to save theatre, we’re still going to do it with everyone else. It’s also important to remember what can happen when we get obsessed with a particular brand of technology.

I guess TV people have been thinking about this too:

http://westernxtheshow.ning.com/profiles/blogs/transmedia-storytelling?xg_source=shorten_twitter

Michael, how did you stumble upon the western x blog post? Amazing. I have no idea what this show is, but i am suddenly intrigued.

I love this idea for character development and audience interaction in art. It is a trickly balance though. You have to create a story that isn’t relient on your audience knowing everything that has been created prior. If your regular plot and character development is severely affected by these types of subplot communications it could throw your audience for a loop and may piss them off. Especially if they are committed to watching the show, but not committed to following online content.

Heroes did this with small webisodes and online comics and it was successful. Then again heroes was very episodic in nature and had SO many plot lines so the approach may not work for all types of work.