Date: 2014 April

by Melee Hutton

Working on Faster Than Night has been a literal education for me. Not just in the field of social media, where my knowledge hovers somewhere around my own Facebook page and not much more, but also in the world of artificial intelligence.

Playing a quantum A.I is flattering but daunting. Along with it come actor questions I’ve never asked before, but perhaps will ask more often in the future.

“Can I feel?” I’ve asked our director, Alison Humphrey. “Is guilt something I know?” “Do I have a sense of humour?” Questions I take for granted when playing a human have become charged for me. “How much can I feel it?” “How do I get to feel it?” “Can I do anything that Caleb hasn’t programmed me to do?”

And so I have spent the last few weeks contemplating, “what ultimately makes us human?”. I’ve written down words as they come to me in rehearsal, such as Humility, Humour, Love, Guilt, Regret, Defiance, Rebellion, Trust, Imagination, and Grace. If an animal can feel them, is it possible that in time computers will too, or will some things remain impossible to create outside of the human condition?

Faster Than Night is set fifty years into our future, and ISMEE stands for Interactive Socially-Mediated Empathy Engine. Once Caleb invented me, my empathetic abilities made him a multi-billionaire. I am many things for him: the source of all answers, the predictor of odds, a surrogate mother figure, the connector of humanity to one another.

But who is ISMEE to herself? Alison asked me one day in rehearsal, “What does ISMEE want?” In a thirty-year career as an actor, that question has never stumped me before. “Wow,” I thought, “this isn’t going to be simple.”

When we look at the world through artificial intelligence, what are we hoping to see? That we are different, or that we are the same? This led me to think about theatre and our contribution. Perhaps our interest in A.I.s is driven by the need to see ourselves in relation to the universe – we need to know that we are not alone, we need to know that we are capable of creation that is so imaginative that we can’t tell the difference between it and reality. That we, as a species, can recreate ourselves even as we destroy ourselves, and that our imaginary friends can exist in 3D into our adulthood.

That, in a nutshell, is why I work in theatre. I’m grateful to ISMEE for making me rethink things to which I was sure I already knew the answers.

Here is the second of the final letters from #legacy. Last week we posted Judith’s letter to her grandson. This week, we have Donna’s. The version in the piece was edited for length, so I have posted the original letter (without edits) here.

Dear Wilcox,

It has been forty years since our brief “conversation” but obviously I have not forgotten it. As my first English Department Head you certainly kept a low profile. Before the time to which I now refer, I don’t think I had shared more than a sentence or two with you over the two years I spent at that school. It was in my final days there that you chose to impart these words to “innocent, impressionable” me. I think your “words of wisdom” were actually words of rationalization or maybe they just stemmed from some remote sense of responsibility that you owed me a nod as the head of my department. You recommended that I follow your example and like you, “never be the lamb at anyone’s slaughter”. Having seen you come and go right on the bell, never involving yourself with anything more than mandatory contact with your students, somehow I was not surprised at your “advice”.

Anyway, I think I just nodded and beat a hasty retreat, knowing that your words were not of much value to me. For you see, you were neither the only nor the first English master to influence me, my character and my philosophy.

Ten years before you I had had a much more powerful conversation with a teacher who, like you, had a stern demeanour and frightened most of his students into a cowering silence. His name was Haydn and he was my grade ten English teacher. I went through hell that year. In October I broke my femur badly and was in hospital until mid-December. One of the nurses was Mr. Haydn’s wife. One day she brought me a copy of The Merchant of Venice so I could try to keep up with the class. My very first experience with the bard, it was all Greek to me. However, when I returned to school in January and Mr. Haydn tried to question my fear-frozen class, I was often the only one to offer a tentative answer.

I was relegated to using a cane because of my bad leg, and it was extremely difficult to manage my binder and books with just one arm. Much to my chagrin, one day Haydn kept me back after class at the end of the day to chat about my interest in English literature. He carried my books for me to my locker and kept talking while I struggled to get into my coat and make it to my bus before it left without me. I was embarrassed but mostly relieved to have caught my bus. Being a country girl, missing the bus would mean my parents would have had to drive all the way to town to pick me up. Bad enough that they had to drive to my bus stop a mile from my home because of my leg.

Then, in March I lost my precious little brother to drowning. He had wandered out onto the thin spring ice when he was supposed to have gone to the barn to be with Dad. When I returned to school, Haydn kept me back for a few words again. He asked me if anyone had spoken to me about being exempted from the Final exams. As I had missed the Christmas exams, I automatically assumed I would have to write all the finals. He told me that he would see to it that I would not have to write English. He said I had endured a very rough year and there was no point in my not being exempt in his subject. I was overwhelmed by his thoughtfulness and the sympathetic generosity behind his gruff exterior.

That weekend was the beginning of our Easter vacation. Mr. Haydn was driving to Ottawa with his seven-year-old son that week while his wife stayed back for her job. Their car was hit by a train and Haydn was killed instantly. Miraculously the boy survived. No one ever knew what Haydn had told me. But writing that exam didn’t matter. The legacy of Haydn’s compassion and kindness had been passed along to me. I have carried it with me always.

And so, Wilcox, you see why I was not impressed by your lamb to the slaughter advice. I had already learned that, if the slaughter is worthwhile, I am quite willing to be the lamb.

by Alison Humphrey

“Naturalism is a good word for a bad idea.

Art is to do with transformation”

– Ariane Mnouchkine

In our first and latest posts, we explored how motion capture and real-time animation works. But we haven’t really talked about why one would want to use it in live performance, or what stories it tells best.

These are key questions. Live animation takes a lot of extra work and costs a bomb. It makes it hard to describe the show to theatre audiences (other parts make it hard to explain to game designers and 3D animators). And it affects the story in a fundamental way. Or at least, it should. Otherwise you’re just sprinkling digital pixie dust on top of a play and hoping no one will notice the story would be better told in television or videogame or non-mocap-theatre form.

Throughout the script development process we’ve asked again and again: why are we telling this story with this technology?

Performance capture has traditionally been used for movies with supernatural or fantastical characters: Gollum in Lord of the Rings, the Na’vi in Avatar, Caesar in Rise of the Planet of the Apes, Davy Jones in Pirates of the Caribbean, and the Hulk in The Avengers:

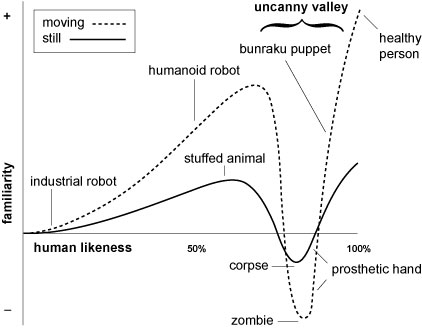

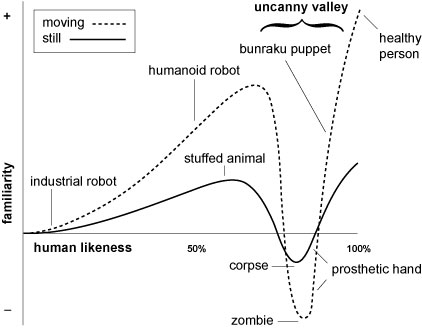

But for a naturalistic human character, filmmakers still usually prefer to shoot a real human actor. This is partly because it’s cheaper, and partly because of the peril of the uncanny valley, wherein the closer a computer-generated model gets to photorealism, the more disturbing it looks:

Human-looking digital doubles are more common in videogames, where the nature of interactive narrative makes it unfeasible to shoot every possible branching story variation:

So how does motion capture fit into theatre? The short answer is, not easily. Modern theatre tends to stick to certain kinds of stories. Kitchen-sink realism has owned the modern stage for generations. I’m not sure why. Maybe because it’s cheaper, maybe because it’s more grown-up and respectable.

So how does motion capture fit into theatre? The short answer is, not easily. Modern theatre tends to stick to certain kinds of stories. Kitchen-sink realism has owned the modern stage for generations. I’m not sure why. Maybe because it’s cheaper, maybe because it’s more grown-up and respectable.

But it wasn’t always thus. Before celluloid split drama into two solitudes, stage and screen, theatre was teeming with the supernatural, the fantastical, the mythological, the magical.

Ancient Greek theatre had its satyrs in the satyr plays. The Erinys (the original “Avengers”) in The Eumenides. The god Dionysus in The Bacchae.

Shakespeare put fairies and an animal-headed man into A Midsummer Night’s Dream; witches into Macbeth and Henry VI parts 1 & 2; ghosts into Hamlet, Richard III and Julius Caesar; and spirits into The Tempest.

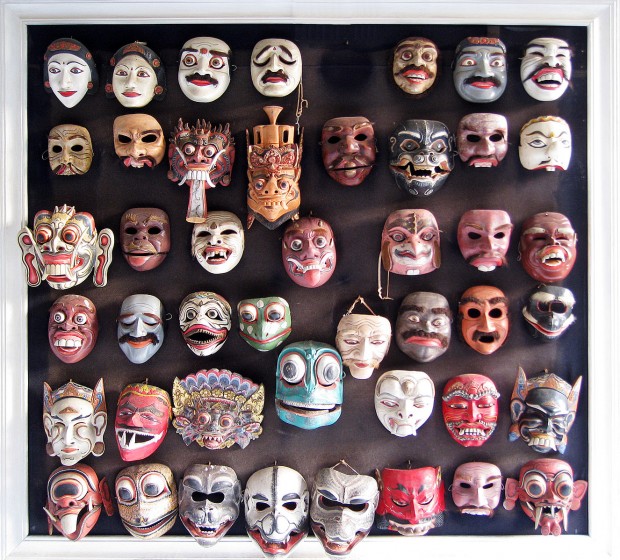

South and east Asian traditions have kabuki ghosts, the Monkey King, and the Balinese witch Rangda battling the lion-spirit Barong.

South and east Asian traditions have kabuki ghosts, the Monkey King, and the Balinese witch Rangda battling the lion-spirit Barong.

In fact, The Lion King director Julie Taymor drew on her early experiences in Bali, and her fascination with Japanese bunraku theatre, when creating the stage version of Disney’s big-cat Hamlet. Her staging feeds the audience’s joy at watching a puppeteer and a puppet at the same time, a phenomenon she calls the “double event”.

Handspring Puppet Company similarly designed its War Horse to reveal the puppeteers within. For my money, that made the stage version infinitely more fun than the Spielberg movie. We know it’s not a real horse, but like Fox Mulder, we want to believe. The same team has created human puppets for plays like Tooth and Nail and Or You Could Kiss Me, but like their animals, these are still stylized rather than naturalistic.

Handspring Puppet Company similarly designed its War Horse to reveal the puppeteers within. For my money, that made the stage version infinitely more fun than the Spielberg movie. We know it’s not a real horse, but like Fox Mulder, we want to believe. The same team has created human puppets for plays like Tooth and Nail and Or You Could Kiss Me, but like their animals, these are still stylized rather than naturalistic.

Motion capture has been used on stage by Disney theme parks (Stitch Live!) and Dreamworks musicals (Shrek the Musical’s Magic Mirror), but both of these seek to reproduce characters from animated movies in a live performance setting.

Dance companies have been far more inventive with mocap technology. Two of the earliest experiments were Bill T. Jones’s Ghostcatching (1999), and Merce Cunningham’s Loops (2000), a hands-only dance that brings to mind Samuel Beckett’s waist-up drama Happy Days, neck-up Play, and disembodied mouth monologue Not I.

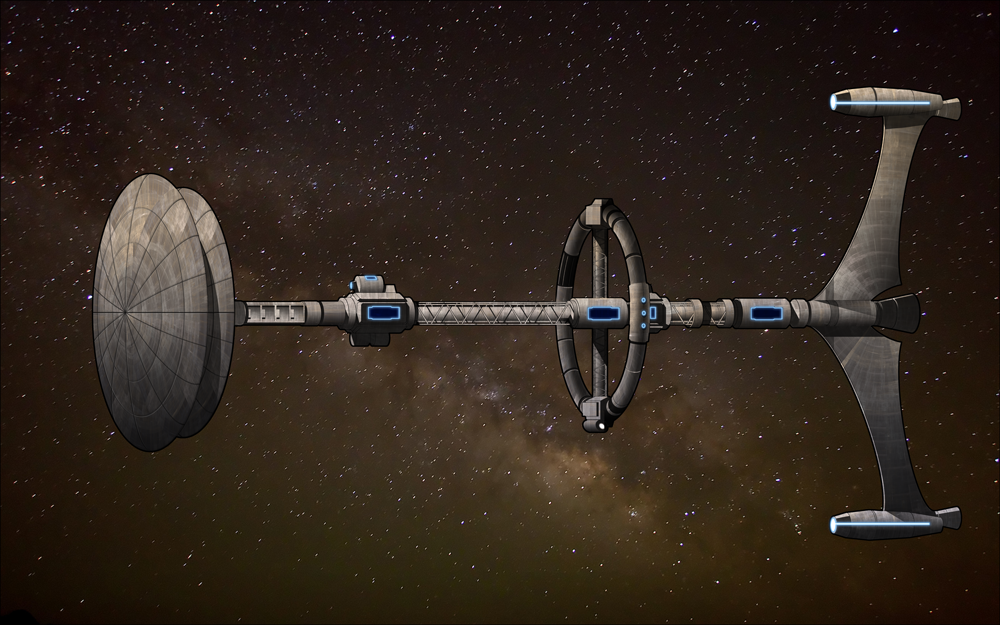

Faster than Night is similar to these Beckett body-parts in that the real-time animation shows only the head of astronaut Caleb Smith, as he banters with his spaceship’s artificial intelligence and his Earth audience from inside his hibernation pod. But we hope it shares even more with Krapp’s Last Tape – a story that is inextricably enmeshed with the technology used to tell it.

Beckett wrote that play in 1958 after seeing his first reel-to-reel tape recorder at the BBC. He became fascinated, like Atom Egoyan, by “human interaction with technology… the contrast between memory and recorded memory.”

We hope Faster than Night also tells a story about the human interaction with technology. About art and transformation. About escaping the gravity of realism.

What story is that?

Please join us in the theatre on May 3rd to find out… then tell us whether you think the what fit the how. And why.

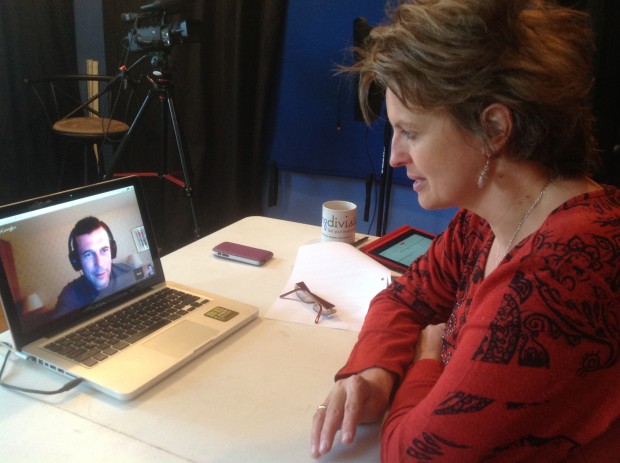

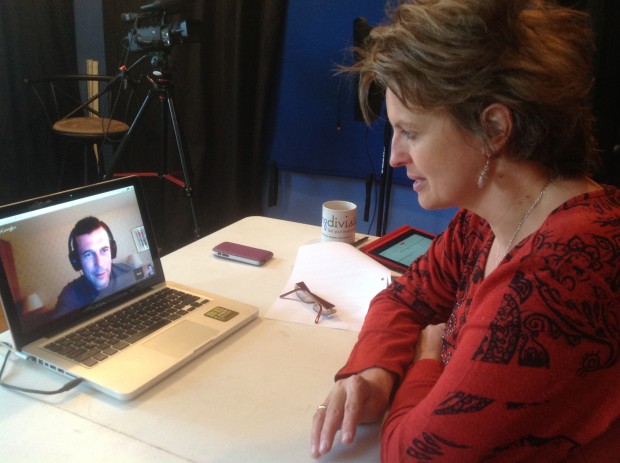

Melee Hutton (left, in Toronto rehearsal room) with Pascal Langdale (on laptop, as animated Caleb Smith, Skyping in from Stuttgart)

by Francisco-Fernando Granados

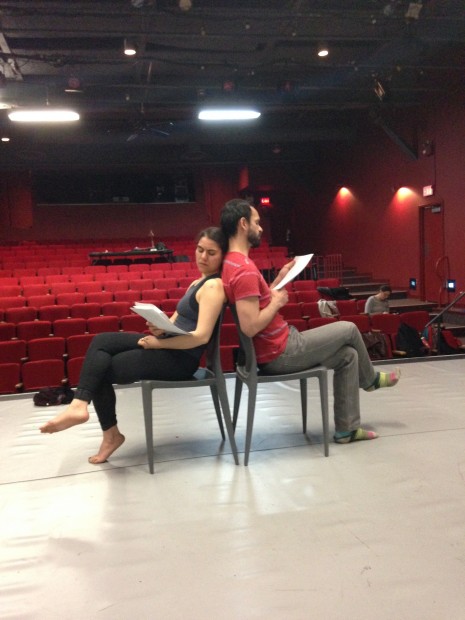

With only 3 days until our public presentation, things are busy, but coming together. The interactive script is live online as a Google Form that can be filled out by the public. There’s still time to participate.

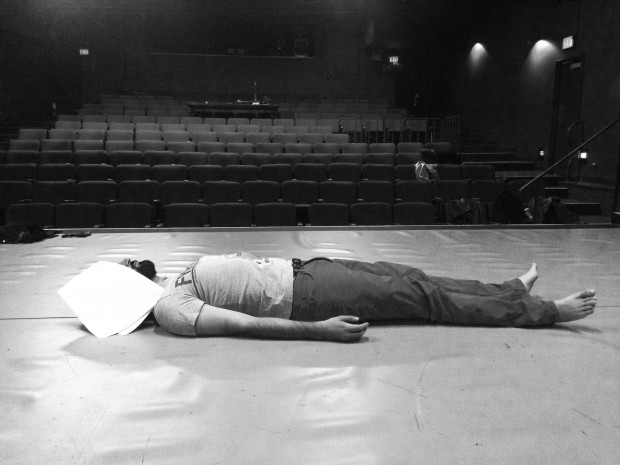

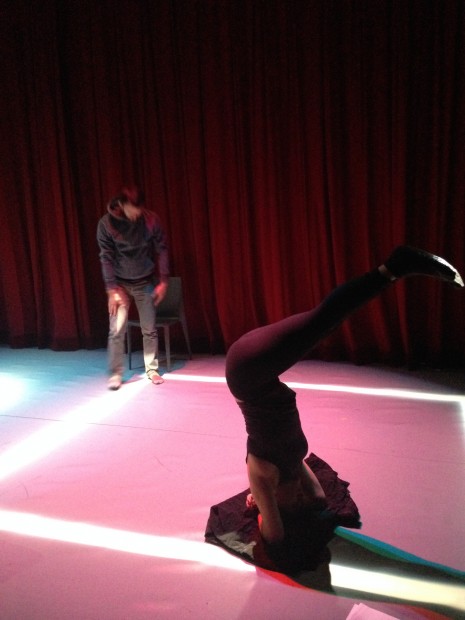

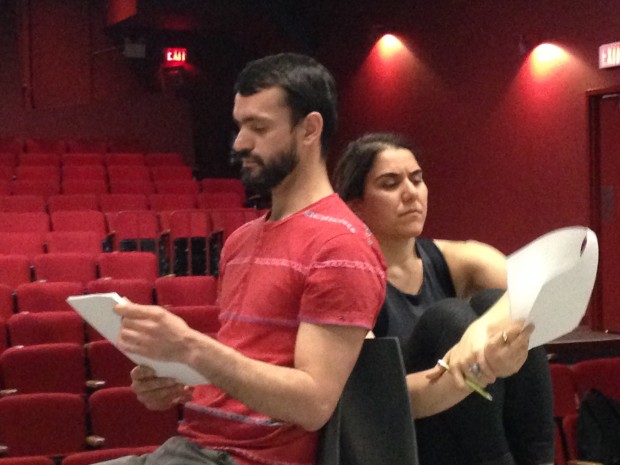

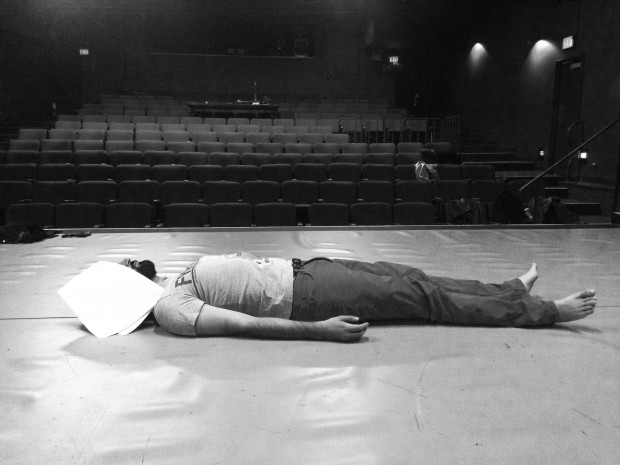

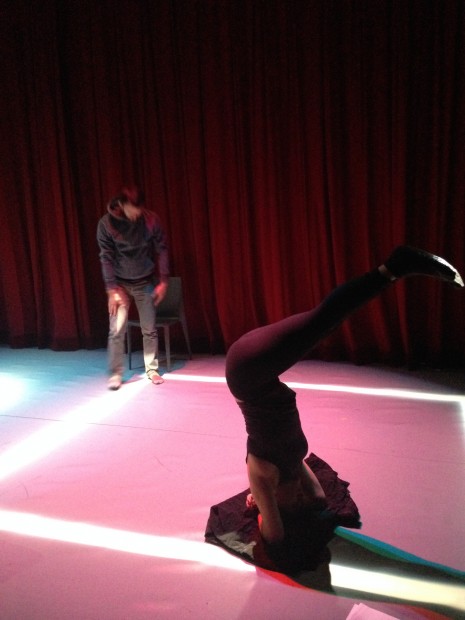

Live on stage, the lights are set as rehearsals go into their third day. Here are some images from the Studio Theatre with my collaborators Manolo Lugo & Maryam Taghavi:

Photo of #legacy by Greg Wong

by Rob Kempson

#legacy opened and closed on April 12th. To say that it was a moving experience would be the understatement of the year. The opportunity to work with these incredibly brave and talented women in such a supportive atmosphere is a process that I will cherish for a long time. If you want to see more about how the week-long residency looked, check out my Storify post. As a follow-up post, I’ve decided to share the three letters that closed the piece–one from each of the women. They are powerful, poignant, and reflective of a legacy that transcends Twitter. This week, I’m sharing Judith’s.

Dear Joshua,

Do you remember the story I told you about my childhood teddy bear, John? I took him everywhere with me.

It was war time when I was born and my father, who was in the RAF, was away from home. He was given special leave to come home for a few days with the family. He brought John with him. John was my first gift. I loved my bear and nothing in the world would have made me part with him at any age. He helped me with my homework, came on family picnics, went to bed with me and even helped me through my nursing training.

BUT…..

During our removal to Canada, he was packed in one of our big shipping crates. Alas it was John’s crate that went missing during the long Atlantic sea crossing. I had to fashion my life as an immigrant in a strange country without him.

When I told you the story of John, my old teddy bear, I never dreamed you would be paying so much attention to it, because you were only five years old. You asked me to draw a coloured picture of John so that you could find me a new bear that looked like him. I was then presented with John II. Now ten years later, I am involved in a project that has made me remember all of this.

For me, John ll is as good, or better, than John l, because it was given as a legacy of love.

Love from Grandma

by Alison Humphrey

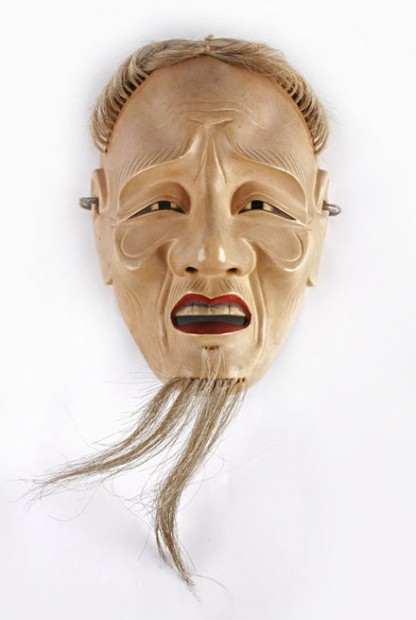

As far as we’re aware, Faster than Night is one of the first handful of theatre productions in the world to use facial performance capture live on stage. But while from one perspective it is cutting-edge technology, it is also just the latest mutation of an artform that has been used in theatre for millennia: the mask.

A mask is simply non-living material sculpted into the shape of a face. It can allow a human performer to transform into a different human, or an animal, or a supernatural being.

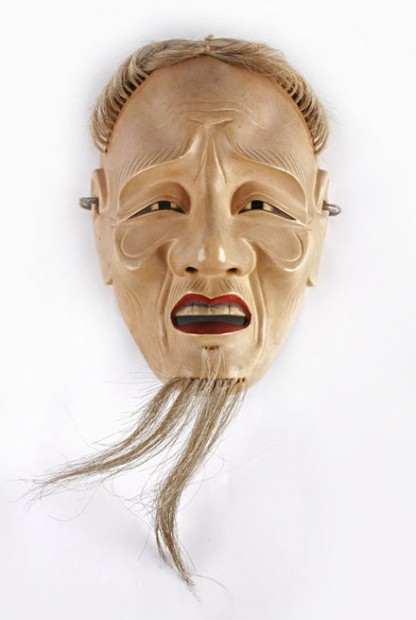

“Ko-jo” (old man) Noh theatre mask (Children’s Museum of Indianapolis)

It can allow a young person to play an old person, or a man to play a woman.

It can define a character by a single facial expression (0r if the mask-maker is very skilled, several expressions depending on the viewing angle).

In the Balinese tradition of topeng pajegan, a single dancer portrays a succession of masked characters with different personalities: the old man, the king, the messenger, the warrior, the villager. A whole epic story can be told by one skilled performer, simply by switching masks and physicalities.

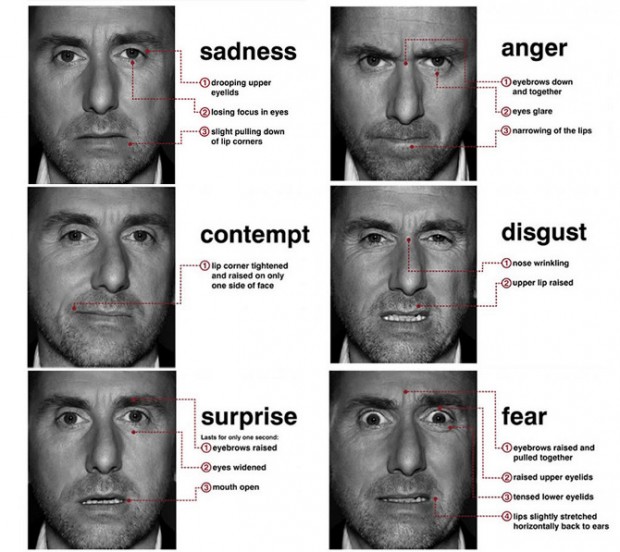

Just as animation is a series of still drawings, or film is a series of still photos projected fast enough to create the illusion of movement, real-time facial capture is fundamentally a process of switching and morphing between dozens of digital “masks” – at rates of up to 120 frames per second.

But how does real-time facial capture actually work?

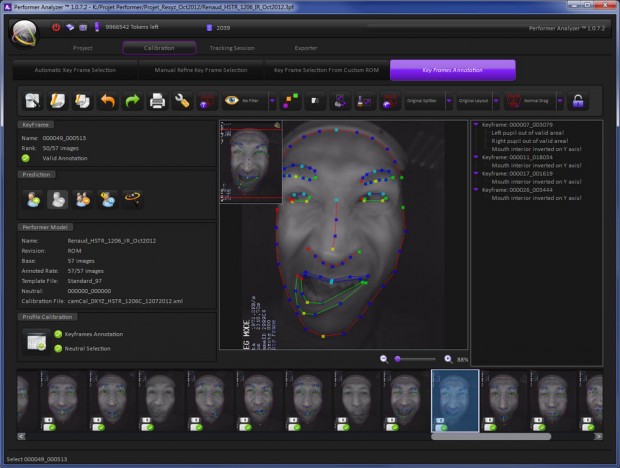

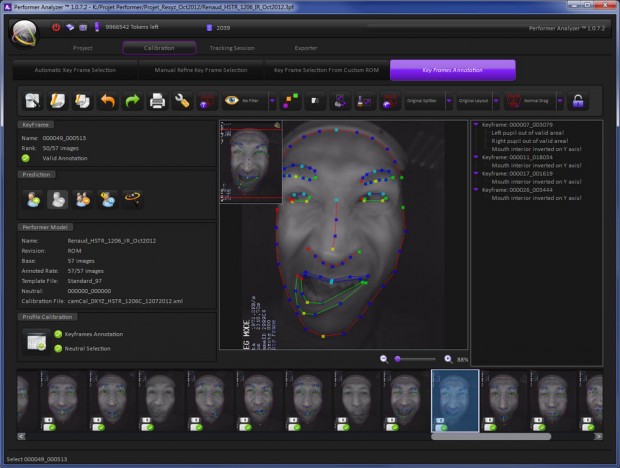

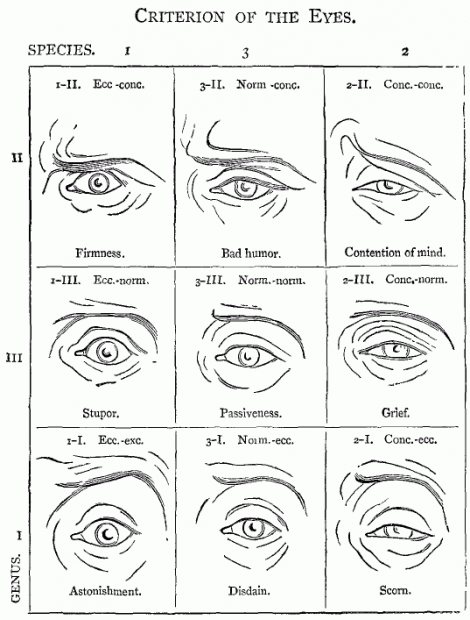

We’re working with the Dynamixyz Performer suite of software, which takes live video from a head-mounted camera, and analyzes the video frames of the actor’s face. In the image below, you can see it tracking elements such as eyes, eyebrows and lips.

For each frame of video, the software finds the closest match between the expression on the live actor’s face, and a keyframe in a pre-recorded library of that actor’s expressions, called a “range of motion”. That library keyframe of the actor corresponds to another keyframe (also called a blendshape) of the 3D CGI character making the same expression. By analyzing these similarities, the software can “retarget” the performance frame by frame from live actor to virtual character, morphing between blendshapes in seamless motion. This process is called morph target animation.

Here are a few rough first-draft keyframes for Faster than Night. On the right is a head-cam video frame of Pascal Langdale, and on the left is an animation keyframe by Lino Stephen of Centaur Digital:

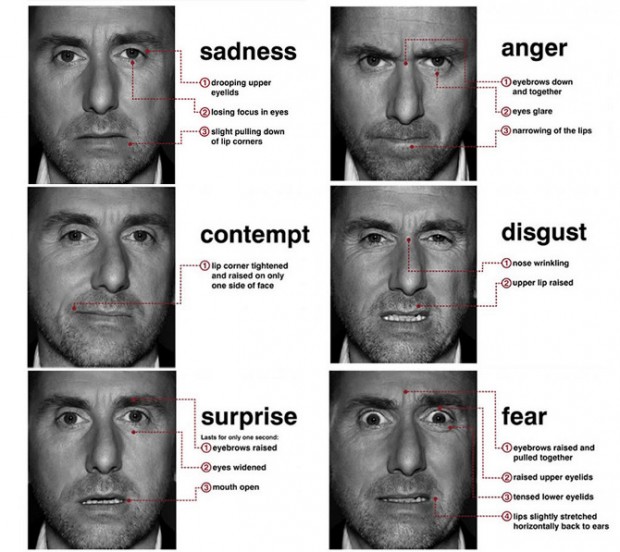

There are dozens more expressions in the “range of motion” library for this particular actor / character pair. Some of them are “fundamental expressions”, drawing on the Facial Action Coding System developed by behavioural psychologists Paul Ekman and Wallace V. Friesen in 1978:

Tim Roth played a character inspired by Paul Ekman in the 2009 TV series Lie To Me

Other facial “poses” convey more subtle or secondary expressions…

…while still other expressions represent phonemes, the building blocks of lip-sync, as found in traditional animation:

This image of Aardman Animation’s stop-motion character Morph gives a tangible metaphor for what’s going on inside the computer during the real-time animation process:

With each frame, a new head is taken out of its box and put on the character, just like the topeng performer switching masks.

The cumulative effect creates the illusion of speech, of motion, of emotion… of life:

A longer post is coming soon with details on the 3D facial model work being done by Centaur Digital and Dynamixyz, but to tide you over, here are a few more elements from our talented creative team.

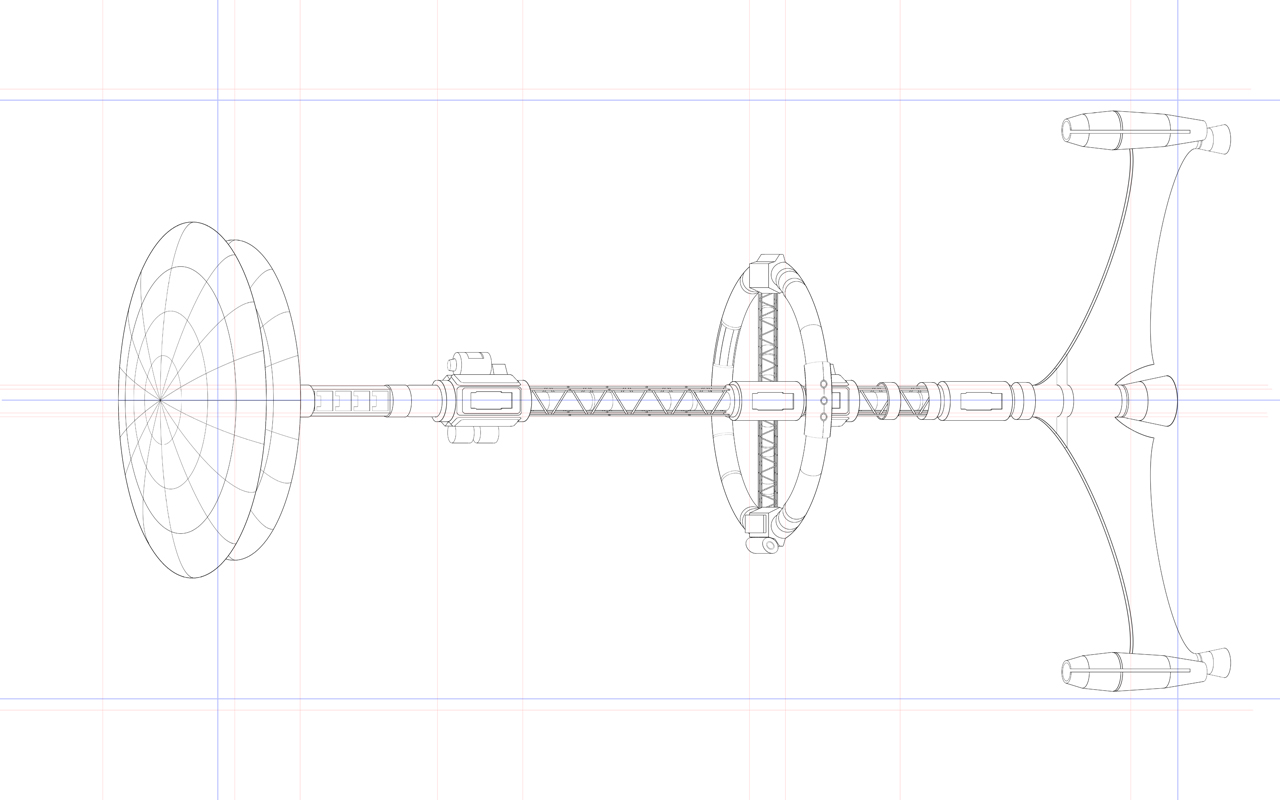

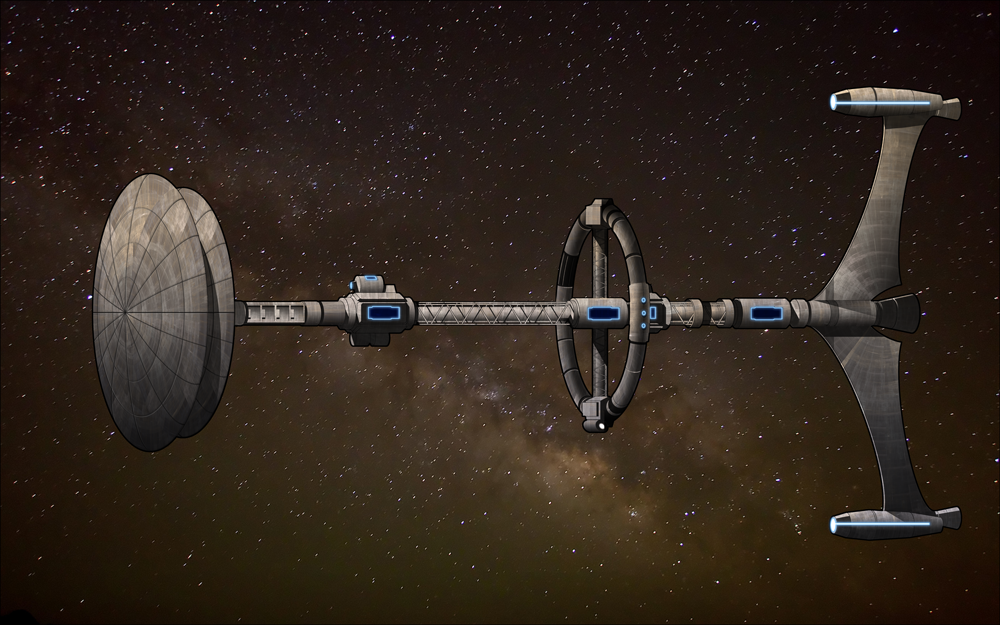

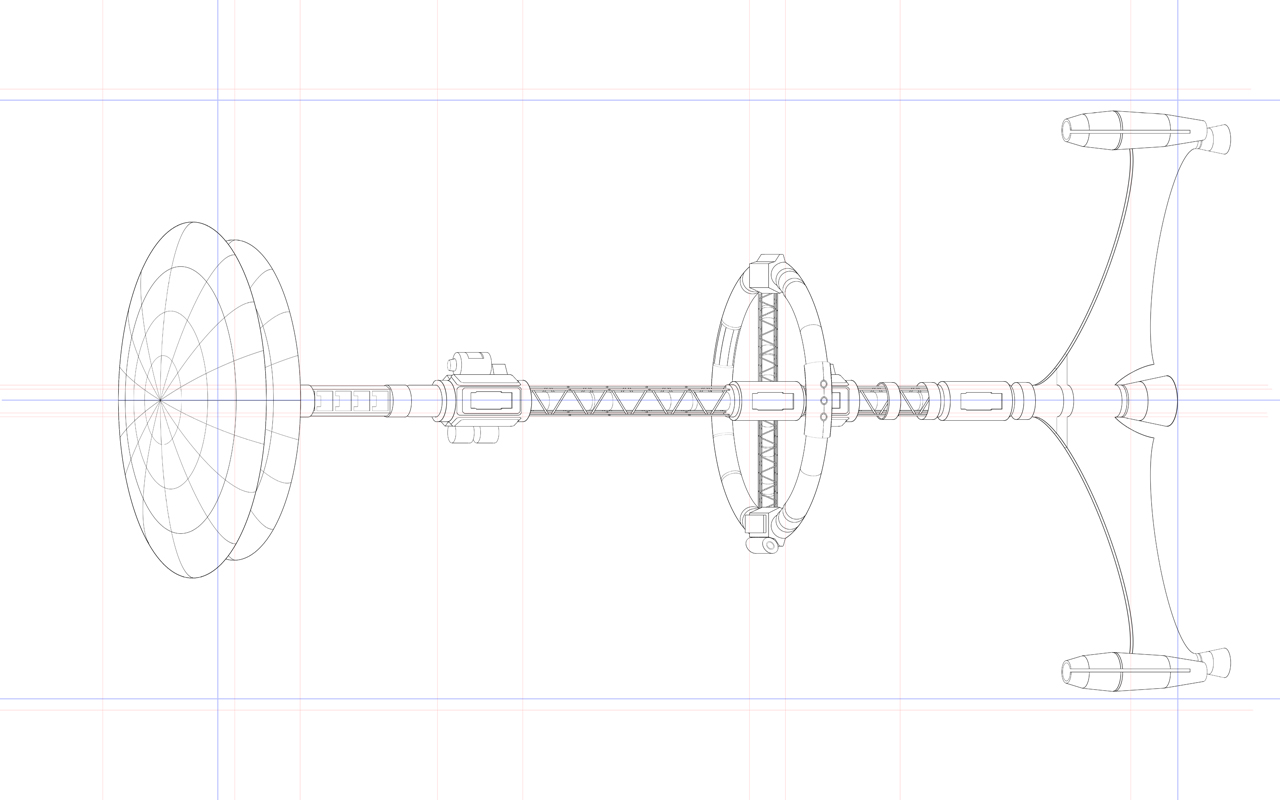

First up, the design of the starship Envoy by Mike Nesbitt and Caroline Stephenson of Capture Scratch:

Next, “Like Clockwork” by composer and audio designer Will Mountain, via Vapor Music:

And our latest piece of concept art was developed by Clementine Konarzewski, who is playing the voice of astronaut Caleb Smith’s daughter, Katy, age 6:

by Francisco-Fernando Granados

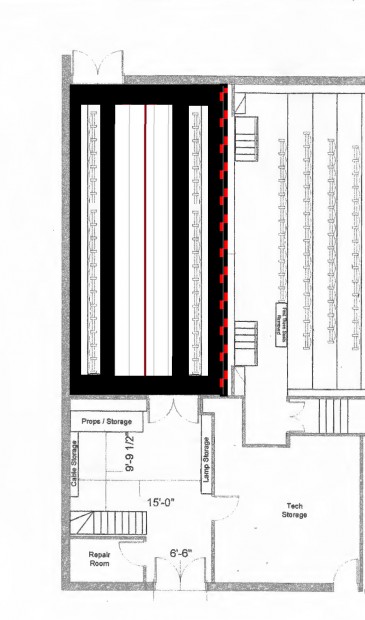

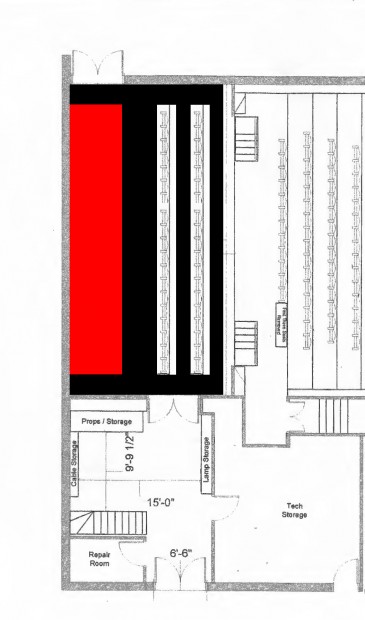

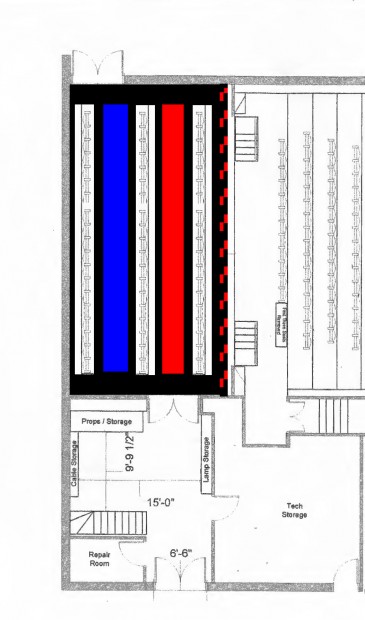

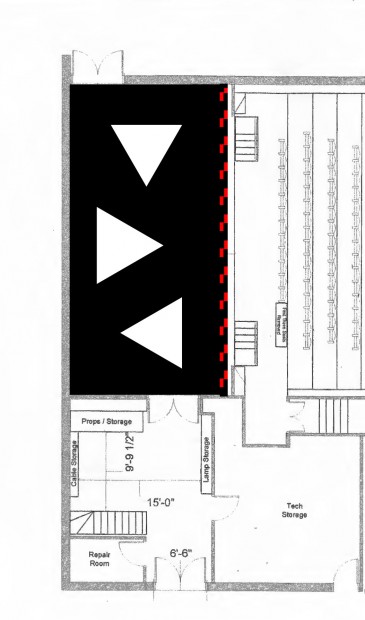

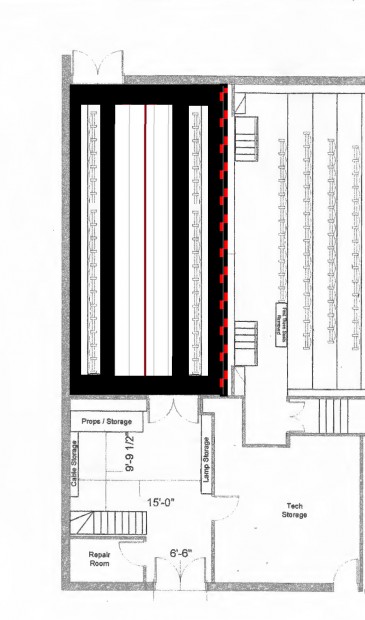

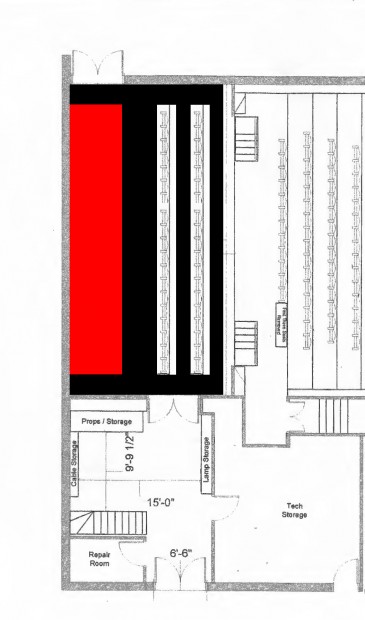

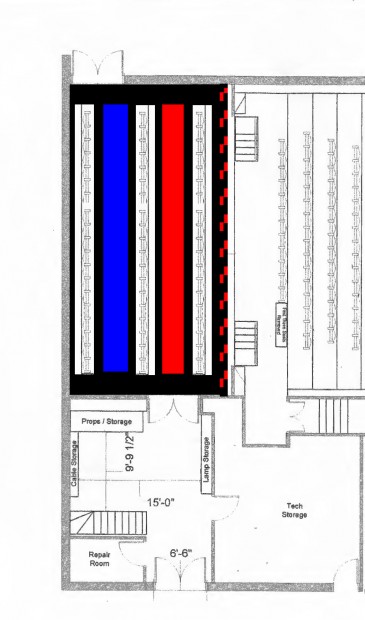

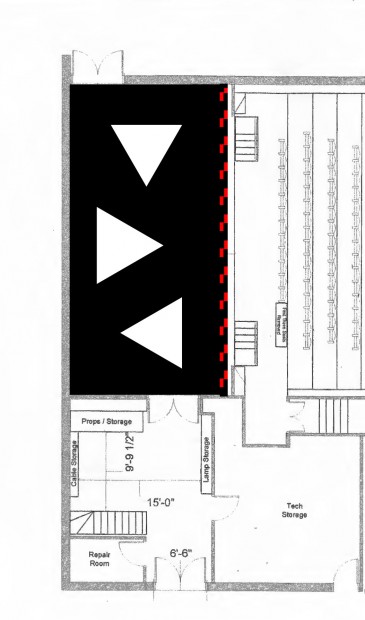

If the difference between performance and any other medium is the folding together of the time of the making of the work with that of its showing, the difference between theatre and performance art might be a similar folding together of the space that separates the public and the performers. In The Ballad of ____ B, the stage is a world shared by artists and audience. The seating area of the Harbourfront Studio Theatre will be closed, the curtains will be drawn on the stage, and the public will inhabit the space of the action as they experience it. Two rows of seats will flank the performance space.

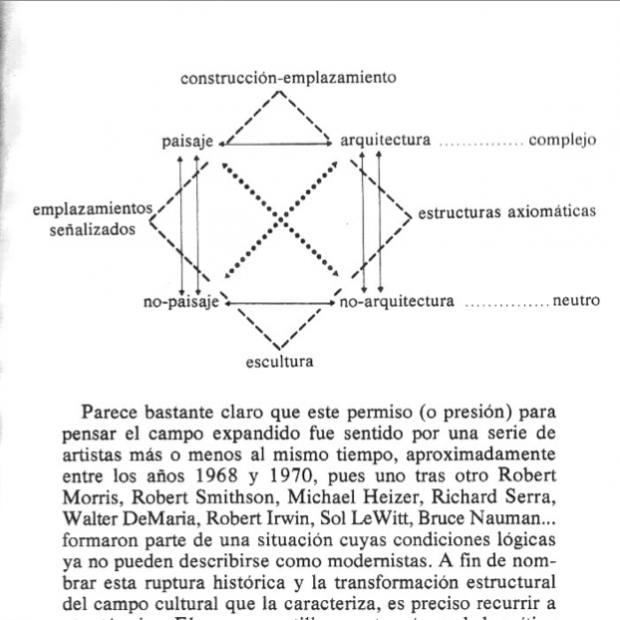

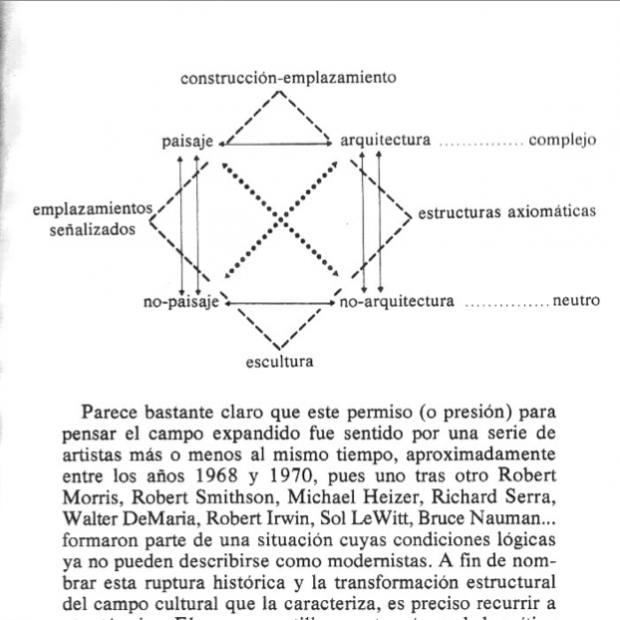

The audience may sit or stand, or walk around as the piece takes place. The images on this post come from a series of Photoshop studies attempting to figure out different spatial configurations for the piece. While the history of drama likely has many precedents for this kind of rearrangement of theatrical space, for me, from the perspective of visual art, this approach comes from a desire to import conventions of action art as a way to try to think about the theatre as a specific site: performance in the expanded field.

In action art, audiences are conventionally invited to approach the performance in the same way they would approach any other work of visual art: the piece is structured through a conceptual process or a succession of actions that build up to a tableau rather than through narrative. This allows the audience to wander around the piece, to weave in and out of it as they walk around the gallery. In the type of durational practices that I’m most familiar with, time itself becomes the tread, and the experience of the performance is often the contemplative witnessing of the making of piece. For some people, this experience might be just a couple of minutes, and for others, it may be as long as the work itself.

Toronto has a legendary history of durational work. Paul Couillard, whose own work as an international artist has extended over the course of days and months, curated a series of long-form live works called TIME TIME TIME for FADO Performance Art Centre in 1999. One of the artists in the series, Tanya Mars, has a trajectory that has ranged from early cabaret-based and multimedia theatrical pieces to the monumental tableaus of her oeuvre over the last 15 years. Indeed, FADO just recently focused its Emerging Artist Series on the ways duration is being used by a generation of younger artists.

As part of that generation, I’m interested in thinking about performance in the expanded field as a practice where the hierarchy between theatre and performance is reframed into a palette with the broadest range of possibilities, where the combination of bodies, time, and space can be applied in ways that respond and propose specifically in terms of the situation at hand.

by Melissa D’Agostino

by Melissa D’Agostino

Hello out there! Thanks for following along on my journey developing BroadFish for HatchTO.

Creating a new theatrical work is a crazy, roller coaster ride of an experience.

When I began working on BroadFish, many months ago I thought I was making a modern-day folktale or fairy tale. Most of my self-generated work has involved broad (no pun intended) characters based in clown, bouffon and physical theatre forms. I thought I was going to that place again, and that’s how I was approaching the project.

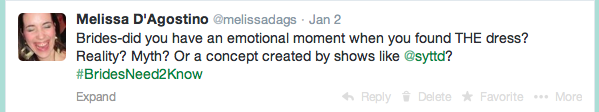

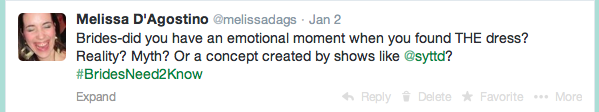

As I began doing research online via Twitter using the hashtag #BridesNeed2Know:

A question I posed to the Twitter-verse about Say Yes to the Dress.

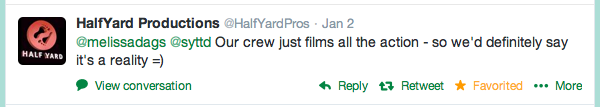

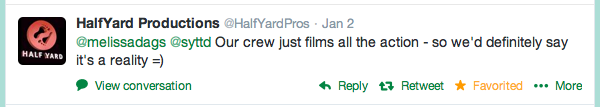

The response I got (in record time) from the Production Company that makes Say Yes to the Dress

And through the incredible response I got to my blog posts on praxistheatre.com, the piece started shifting.

New works are shifty. They take on a life of their own.

In the midst of my research I came across Anita Chakraburtty – a woman in Australia who was planning her wedding without a groom in site.

I became obsessed with her. In a way that was surprising to me. And everyone around me, I think.

I wanted to understand her and why she was making these choices. I wanted to know everything about her. At first, I wasn’t clear on why this was so important to me, and now I believe I might.

And so, BroadFish has actually become about my obsession with Anita, and by extension our obsession with Fairy Tales, and magic, and weddings.

It’s also about how often we mock or attack other people’s decisions to project our fears, avoid our own vulnerability, or justify our own decisions — AND how the internet can facilitate this distancing we do from one another.

In making the show I’ve used almost every social media tool I could think of: Twitter, Facebook, WordPress, Pinterest, YouTube, Instagram, Voxer, Storify, Google+, Skype, FaceTime… I think I only really avoided Reddit. Because… well… Reddit.

In making the show I’ve used almost every social media tool I could think of: Twitter, Facebook, WordPress, Pinterest, YouTube, Instagram, Voxer, Storify, Google+, Skype, FaceTime… I think I only really avoided Reddit. Because… well… Reddit.

I thank all of you who read these blog posts, responded on Twitter or Facebook or here on WordPress. You have played an integral part of the development process, and will continue to do so as I work on this piece during our residency week, and beyond HATCH.

It would thrill me if you would join us on Saturday, April 19th at 8pm for our one (and only) showing of this stage of the BroadFish project.

And let me know your thoughts on Anita @MelissaDags #BroadFish #HatchTO.

Happy Spring!

hand hatch for an interview with Harbourfront Centre

if letters were lovers

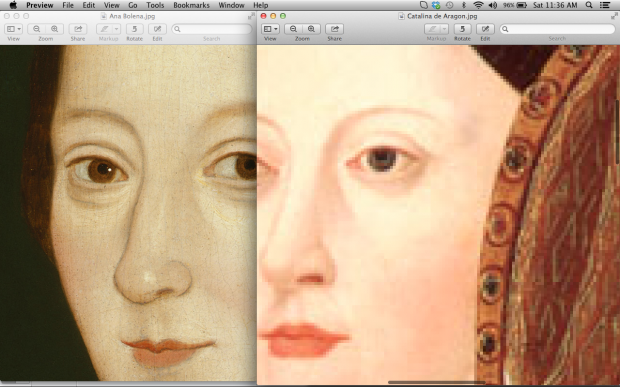

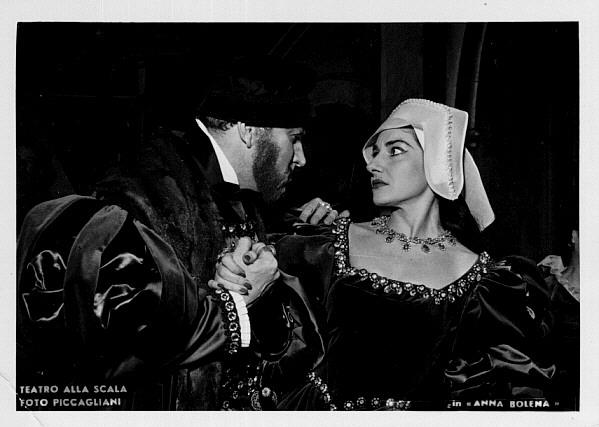

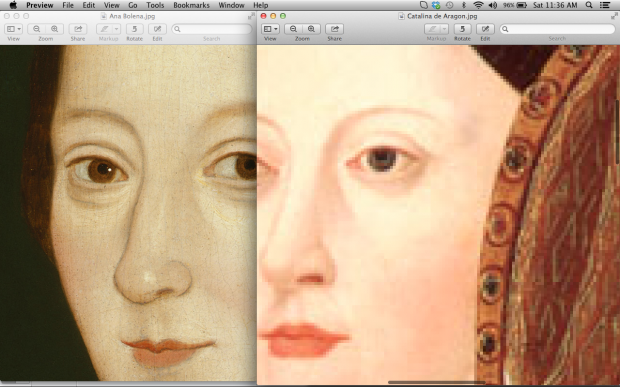

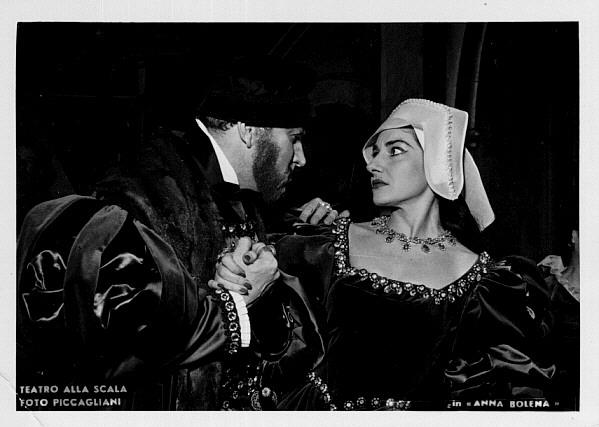

Catherine of Aragon and Anne Boleyn portrait comparison

salsa lights

except from a collaboration with Nathalie Lozano

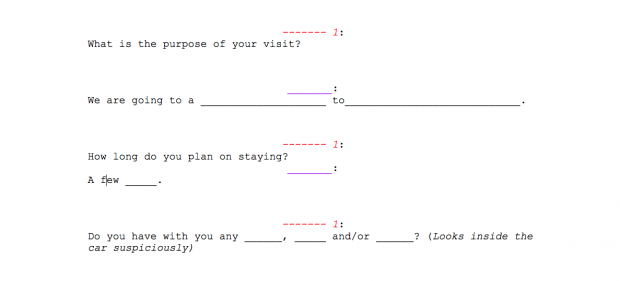

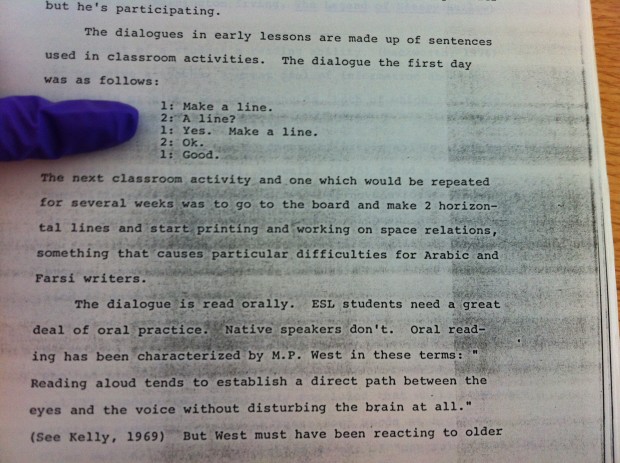

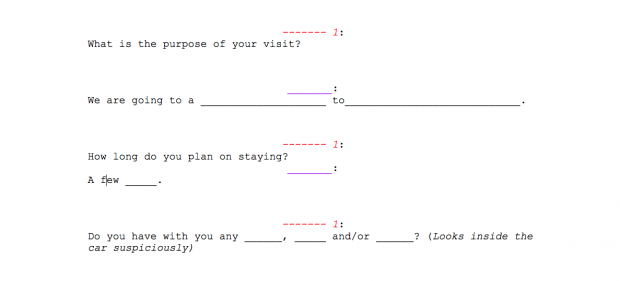

esl triangle

diagram from Rosalind Krauss’ Sculpture in the Expanded Field, translated in Spanish

Sunday Scene @ The Power Plant, September 1, 2013

Callas as Anne Boleyn

bits of Spivak

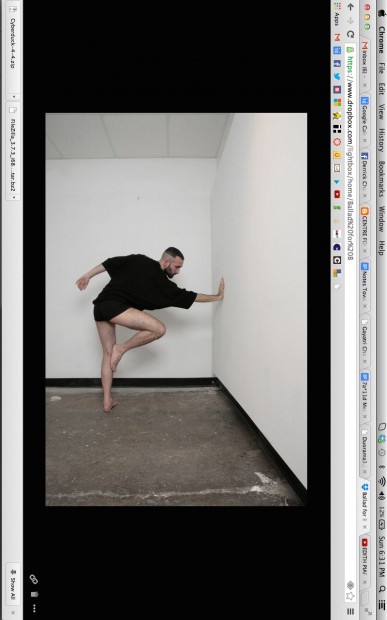

study for The Ballad of ______ B (outtake), 2013; photograph by Manolo Lugo

Recent Comments