Category: Lindsay Schwietz

(l-r) Rosa Laborde, Carlos González-Vió and Zarrin Darnell-Martin in Beatriz Pizano’s La Comunión

by Lindsay Schwietz

In part two I continue my discussions with four women who are working in theatre in Toronto – their views on the status of women, feminism, and their experiences working in theatre. In part one I interviewed Donna-Michelle St. Bernard and Erin Shields.

Beatriz Pizano

Beatriz Pizano is feeling good about the status of women in Canadian theatre. “It’s very exciting for me. I see a lot of women emerging as writers and directors. When there are obstacles there is a greater opportunity for another kind of art to emerge. You either forget about doing anything or you do something about it.”

For Pizano, though, being a woman wasn’t the issue – being a culturally diverse artist was. When she came to Toronto in 1991-92 it was really hard for her to find work and make it as an actor. The desire to create her own work came from the lack of opportunities for her to tell the stories she wanted in the ways she wanted. “I think it’s very important to support women doing their own work. If you wait for someone to offer you a job – I’m not interested in that.”

Pizano is a playwright, a director, an actor, and the Artistic Director of Aluna Theatre, a Colombian-Canadian Toronto-based theatre company. She travels regularly to international theatre festivals and is heading to Bogota, Colombia in November to attend a women’s festival. “I’m very happy with what I’m doing. I collaborate with some amazing women, specifically in Colombia, who have taught me a lot about women who fight for other women – women who have death threats because a certain group considers it feminist. They continue to do theatre because they believe in what they’re doing.”

However, it is not about politics for Pizano, or trying to push a political view, it is about telling the story and giving a voice to those who can’t be heard. “When I write I don’t think I’m writing for women. That gives me a lot of freedom. I’m looking for an individual and a story… they are women’s voices because I am a woman. But they are voices regardless. I want this story to be heard. Maybe one person who sees that has the power to do something. Or we become more aware of what is happening in the world.”

The most important thing for Pizano is to have conviction in what you say you believe in and respect the art and theatre. “I’m in a place in my life where I know I’m changing things with what I’m doing. If I can change one thing then I’ve done a good job,” she says. As one of two recipients of the 2010 John Hirsch Prizes, from the Canada Council – a prize awarded every second year to emerging professional theatre directors – Pizano is being recognized for the changes she is speaking about. The jury spoke of Pizano as “one of the most important directorial innovators in a landscape of new developing artists in Canada. We recognize her ability to galvanize her community with a proactive commitment to process and production.”

This proactive commitment also includes working with younger women. “I love mentoring young women because I learn a lot from them. They experience a world that I no longer experience. I learn a lot from them about how they see the world nowadays. I find young women now are at a much better place than I was at that age. It took me a whole lifetime to figure out what I wanted and women in their twenties are running programs and coming up with so many ideas.”

Kelly Straughan

Kelly Straughan

For Kelly Straughan, it always starts from the art. “Loving the way women write, women’s stories, working with women. If it doesn’t start from the art then I think it’s really hard to keep it going,” she says. “It’s too difficult to do what we do and not really feel moved by the content.”

Straughan is a director, former Assistant Artistic Director at Tarragon, and current Artistic Director of Seventh Stage Productions, a Toronto theatre company that focuses on telling stories about women, by women, and for everyone. Their most recent production, 9 Parts of Desire, showcased the lives of a cross-section of Iraqi women. Seventh Stage Productions started as a collaboration between Melissa-Jane Shaw and Rosa Laborde, bringing Straughan on board after she completed her Masters in Vancouver. “It came out of discussions [Shaw and Laborde] were having and things they were noticing in theatre. They were seeing so many talented women not working enough and finding it difficult to find female leaders.”

Straughan’s training and education were in a very male environment. She had some wonderful mentors, but they were always men and the content that they gave her to work with was very male in its influence and dynamic. Although she learned a lot, she says it was really Shaw and Laborde that made her start to realize that things could be different. “It took me a while to ask – is there a different way? How are women writing? Is there a difference here?”

Her experiences with Seventh Stage Productions have made her look at how content can be influenced by gender.

“It’s not an overt problem anymore. For many years it was an overt problem. Women were actively on the sidelines. Now it’s beneath the surface. We have to look at the fabric of how plays are chosen. What is the nature of art? How do theatres program a season? What are audiences used to seeing? That’s the hardest to actively combat against,” Straughan says. “I don’t ever feel oppressed by men… but the problem is you pick art based on what speaks to you. You can’t help be moved by something that’s in your life experience… as a director you have to be able to get to the heart of the material. So if it truly does not speak to you then it’s really hard to direct it. I do not blame male artistic directors for picking material that speaks to them or excites them.”

This is where women can help each other out. Straughan suggests that being strong together and supportive for other women is really important in order to produce work in Toronto. “I really feel that in my age range, we are really trying to help each other succeed in whatever way we can.” Seventh Stage Productions is in connection with other feminist theatres in places like New York, and Nightwood Theatre in Toronto. “We’re only stronger together,” Straughan says. “We’re always actively trying to take the pool of women who are concerned about this and make sure that we are unified, so we’re never acting against them.”

The Conclusions

Looking at the personal stories and opinions of women working in theatre provides important context when studying the PACT statistics on the lack of women in artistic leadership positions. Although these statistics are at first shocking, there is a thriving independent theatre community with women creating their own work. Women working as directors, artistic directors and playwrights in the larger PACT theatres going forward will be vital in ensuring women’s voices are heard by a wide range of theatre-goers. However, the definition of success or failure is no longer dependent on these theatres alone.

Donna-Michelle St. Bernard, Erin Shields, Beatriz Pizano and Kelly Straughan, are all examples of women who have created careers in theatre by creating opportunities for themselves. Whatever the motivation – be it giving voice to those who don’t have a voice, story-telling, making art, or writing plays to create more opportunities for women – these four artists are among many women who create theatre in this country so they can delve into the issues that are important to them.

When interviewed, Donna-Michelle St. Bernard said “it’s the responsibility not only for the theatre community to value women in the arts, but for the arts to value women in the community.” This is why giving greater voice and creative control to female artists can make theatre better. It’s a way to tell stories and represent women from a female perspective, leading to a greater diversity of authentic voices on our stages, and this diversity can only help us build better plays, and stronger audiences.

Lindsay Schwietz is a freelance writer in Toronto and a semi-regular contributor to praxistheatre.com.

Donna-Michelle St. Bernard onstage with Belladonna and the Awakening at Toronto Rape Crisis benefit

by Lindsay Schwietz

In December I wrote about the lack of women in artistic leadership positions in theatre in Canada. With women holding only around 30% of playwright, artistic director and director positions in PACT theatres – in general, the larger the theatre company the less the women – I was upset. There is such an enormous amount of women in Canada training in the arts, believing in their craft and working hard to make a career in theatre, and it is difficult for me to accept that the opportunities are not there to develop their art. I was disheartened until I decided to sit down with some of the women who are in that 30% in Toronto. What are those women’s experiences working in theatre? What do they believe about the status of women? What are their views on feminism as it relates to their work as artists?

I chose to interview four women in Toronto who are successful in both the independent theatre scene and in some of the larger theatres. They are playwrights, directors, performers, artistic directors, and general managers. They have all chosen to create their own work for various reasons. They are all strong women who believe in what they do and work hard to achieve their goals. They are: Donna-Michelle St. Bernard, Erin Shields, Beatriz Pizano and Kelly Straughan.

Donna Michelle-St Bernard

Because of the stigma attached to the word, women being quiet about their feminist views seems to be a trend in Toronto at the moment. Not for Donna-Michelle St. Bernard. “What happened to ‘Hear Me Roar’?” St. Bernard says. She is a feminist and proud of it. “I’m holding on to the word – I’m not letting it go.” St. Bernard is a playwright, emcee, and the general manager of Native Earth Performing Arts. Working on her goal to write a 54-play series – one play for every country in Africa – and a physical ‘monument of women’ which is still in the conceptual phase, she is focusing on doing more work for women.

When the PACT report came out, she was most interested in the high number of women in administrative roles versus the low amount in artistic roles. She wondered whether many women chose the administrative work when the opportunities were lacking to use their artistic side. “It calls to mind the number of women who work in arts administration who feel stigmatized by their administrative practice and feel it harder to break through the perception of them as administrators to be artists,” St. Bernard says. “For me my practice is a whole person practice. People like to treat my administrative brain and my artistic brain as separate entities, but I’m a whole person.”

Dienye Waboso and Nawa Nicole in Donna-Michelle St. Bernard’s Gas Girls.

Now that the independent theatre scene in Toronto is thriving, more women are able to use both sides of their skills. “You have all these women who have a quiet artistic practice, who’ve now bolstered up their administrative capacities. I feel that is the root of all these independent companies being started by women. ‘I have this skill and I have this skill’,” says St. Bernard. “In theory, in the past it wasn’t that easy or conventional to just start a company to do your work.”

“We need to start validating and valuing independent work done by women because at this moment, independent theatre is our territory,” she says. “The environment is ripe for all these independent companies – for one-off shows. And it’s not just that we can do them. It’s the fact that the press will review a show by a company they’ve never heard of, and the professional community will come out and see what we’re doing even if it didn’t come up through their ranks. In that way I feel really positive about the empowerment of women in the arts.”

In her own work, St. Bernard is completely content with what she is doing and how she is doing it. “The theatre I make happens where I want it to happen in the way I want it to happen. I’m perfectly satisfied. And I’m successful by my definition, in the work that I’m putting out, who’s coming to see it and what the response is to it.” She measures her own success her own way, and does not need the larger theatre houses to validate her. That being said, St. Bernard is conflicted; it still angers her that there is not more artistic work for women in the big theatres. She isn’t producing work at the big theatres because she feels they are not a good fit for one another, but she wishes that were more of a choice rather than something imposed on her and many other women. “I don’t want to be there. But I don’t want to not be there because I’m not wanted there.”

Despite this conflict, what is really important for St. Bernard is being able to do her work and speak up for women’s rights. “Those of us who have the capacity to have voice have the responsibility to carry voice,” she says.

Erin Sheilds and Maev Beaty in Montparnasse

Erin Shields

“In my theatre program there were maybe 70% women and 30% men, but we were doing Shakespeare and Chekhov and all these plays where there were so many more male characters.” Starting as an actor, Shields was enraged at the disproportionate roles for men versus women, and she has seen many women quit because it is too hard to find work.

The answer was to create work for herself and in the past few years Shields has worked her way from the Fringe, to Summerworks, to having her play If We Were Birds on the main stage at the Tarragon this season. “It was always in my brain when writing that I wanted to make a lot of roles for women because I think that’s the way to change things – make good work, and make work where there are lots of women onstage, behind stage and lots of women everywhere.”

Shields notes that theatre training is really centered on “the history of dead white guys”, and that women are expected to adapt to this to survive. “Women are more accommodating in terms of listening to men’s stories. We’re used to hearing men’s stories and thinking of them in terms of ourselves… I can see myself in Hamlet and I can see myself in Othello and I can see myself in Lear. I can identify with these characters. Men have a more difficult time doing that because they haven’t really had to.”

Although not scared to use the term ‘feminist’ in terms of the greater discourse, Shields doesn’t tend to use the word because she feels it puts women in a cage, and suggests that labeling a piece ‘feminist’ can alienate many audience members who could otherwise be moved by it. “It puts up a warning that says ‘oh this doesn’t relate to me’ – for men and for women,” she says. “It can make people disconnect from the get go… you can look at this as a voyeur, but this doesn’t affect you.”

Shields says she is tired of being labeled a ‘female’ playwright. “I guess we have to do that still,” Shields says. She’d rather a world where she is simply a playwright, and it’s just about the art. “If you think of women playwrights who have been very successful, I think they are poets who transcend the women’s stories, but aren’t afraid to have women’s stories. They write plays that are human, not just female.”

Stay tuned for part two, which will include my interviews with Beatriz Pizano and Kelly Straughan.

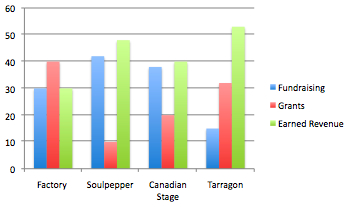

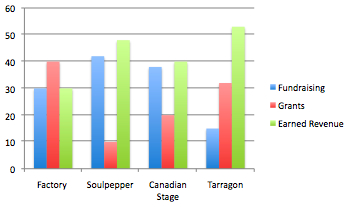

Soulpepper is number one in Toronto theatre in private fundraising as a percentage of revenue (blue).*

by Lindsay Schwietz

Artists have always had issues with finding ways to finance their projects and support themselves. With the Toronto Arts Council reporting the average earnings of Canadian artists to be $23,500* (the lowest 25th percentile of average earnings and hardly an amount to live comfortably by in Toronto), theatres and theatre artists are continually seeking funding through the government, trying to increase their ticket sales and find private donors to support their art.

Soulpepper theatre has created a unique way of dealing with this – the Soul Circle Mentor program. For a donation of over $20,000, a donor can become a “philanthropic mentor” to one of the artists in the Soulpepper Academy. “We wanted to find a way for donors to have more of a one-on-one connection,” says Juniper Locilento, the Government Relations and Foundations Manager of Soulpepper. “So the Soul Circle Mentor program came into existence when the Academy started in 2006. We really saw it as an opportunity, on a bunch of different levels, for some of the donors who are closest to us, to give them an opportunity to connect more closely with these artists who were coming in. And we wanted to give these artists an opportunity to interface and network and just talk to donors so they would become a little more comfortable with that idea.”

The Soulpepper Academy is a group of ten artists (directors, playwrights, designers and performers) chosen from across the country to develop their skills in a two-year fulltime paid residency program at Soulpepper. The first year of the program focuses on training and teaching, with the second year focusing on performance and production. The artists not only get a chance to work with the Soulpepper Company on the mainstage, they also develop a collective creation, which is performed at the end of their two years.

For Mike Ross, being paired with the Youngs meant Raptors tickets, dinners in Rosedale, performing at a birthday party for their parents, and finding backers for his one man show. Photo by Sandy Nicholson

As a major part of their training they are each paired with one artistic member (usually a Soulpepper founding member) and a philanthropic mentor (in most cases a wealthy business couple) by Albert Schultz, the Artistic Director of Soulpepper. The Academy members are required to forge a relationship with the philanthropic mentors they are paired with. This includes talking to them at functions, wine and cheese at pre-openings, dinners together, and sitting with them on opening night –at least once a month, but potentially three or four times a month.

“It was our responsibility to forge a relationship with these people, as it was theirs as well,” says Mike Ross, a graduate of the Soulpepper Academy and a current Associate Artist at Soulpepper. “We were expected to spend time with them. It was actually something that was a little intimidating at first because, although everybody’s there for the same reason, it’s different kinds of people – the artists and often time business-world people. It’s not easy to walk up to someone like that cold and start getting to know them.”

After two years, though, they get over this awkwardness. For Mike Ross, he became friends with his mentors – David and Robin Young of the Young Centre. “We’ve developed enough of a relationship that Soulpepper this season is producing a one man show of mine that they’re the private sponsors for specifically,” he says. “It became a surprisingly casual relationship.”

“I would be very nervous, if it wasn’t for my experience here, going up to what, at that point, I would have deemed just a rich person and asking them for money. I don’t feel that’s the case anymore – I’m asking them to create a relationship, which is a different thing. That’s for them something we can share in. It’s not just handing your chequebook over and maybe giving a shout out on opening night. We’re going to be part of something all together and all get something out of it.”

Soulpepper is thriving. With only 10% of their over 8 million dollar a year revenue coming from government funding, they have obviously found a way to create a sustainable theatre company through their network of private donors – without using tax dollars. They have made relationships with these people who have money to donate and made them part of theatre –made them invested in the arts on a monetary, personal and emotional level. They are teaching developing artists the skills to be able to schmooze and develop relationships with donors and learn the art of theatre as a business.

With Soulpepper it works. They produce classical plays that are generally audience-friendly, with well-known Canadian actors and theatre artists. With plays by Tom Stoppard, David Mamet and Edward Albee, starring actors like Eric Peterson straight from his success on Corner Gas, it’s an easier sell to people outside the theatre community than other companies producing new creations.

But can this model work elsewhere? What about those artists who don’t want to produce classical audience-friendly theatre? Would a business-minded couple be interested in supporting political or experimental theatre?

Mike Ross had a great opportunity to be paired with David and Robin Young, who are devoted and involved with the company. But this method of fundraising raises new questions about creative support: What about those Academy members who are paired with less enthusiastic mentors? What if they don’t get along? What would happen to a student who offended a donor? Or does Soulpepper already ensure that won’t happen by choosing artists that certainly wouldn’t offend donors?

Theatre is created when there is the capital available to create it. There is constantly a struggle to reconcile the need to create art that artists believe in, with the need to finance that art. This isn’t a new problem. Finding money for theatre projects and adapting the product to get that funding is a problem that has been around a very long time. Moliere, Stanislavsky and Shakespeare all forged personal relationships with wealthy elites to facilitate their art.

So this certainly isn’t a black and white issue. One one hand it begs the question, “Has Soulpepper taken the model too far for 21st Century sensibilities? Are they influencing young artists to focus on the sell-ability of their creations over developing new riskier works? It would be simplistic to stop there however, considering the other two major resources for creating theatre: grants and ticket sales. The sad state of arts funding for independent artists in Canada combined with recession-era entertainment budgets leaves few alternatives. Perhaps creating art is living with a series of compromises.

* Data courtesy of theatres and/or the charitable section of the CRA website.

You can read more articles by Lindsay on her own website, Toronto Theatre Thoughts.

Recent Comments