Soul Circle Mentors: Is making friends with wealthy people part of being a theatre artist?

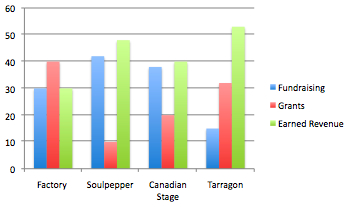

Soulpepper is number one in Toronto theatre in private fundraising as a percentage of revenue (blue).*

by Lindsay Schwietz

Artists have always had issues with finding ways to finance their projects and support themselves. With the Toronto Arts Council reporting the average earnings of Canadian artists to be $23,500* (the lowest 25th percentile of average earnings and hardly an amount to live comfortably by in Toronto), theatres and theatre artists are continually seeking funding through the government, trying to increase their ticket sales and find private donors to support their art.

Soulpepper theatre has created a unique way of dealing with this – the Soul Circle Mentor program. For a donation of over $20,000, a donor can become a “philanthropic mentor” to one of the artists in the Soulpepper Academy. “We wanted to find a way for donors to have more of a one-on-one connection,” says Juniper Locilento, the Government Relations and Foundations Manager of Soulpepper. “So the Soul Circle Mentor program came into existence when the Academy started in 2006. We really saw it as an opportunity, on a bunch of different levels, for some of the donors who are closest to us, to give them an opportunity to connect more closely with these artists who were coming in. And we wanted to give these artists an opportunity to interface and network and just talk to donors so they would become a little more comfortable with that idea.”

The Soulpepper Academy is a group of ten artists (directors, playwrights, designers and performers) chosen from across the country to develop their skills in a two-year fulltime paid residency program at Soulpepper. The first year of the program focuses on training and teaching, with the second year focusing on performance and production. The artists not only get a chance to work with the Soulpepper Company on the mainstage, they also develop a collective creation, which is performed at the end of their two years.

For Mike Ross, being paired with the Youngs meant Raptors tickets, dinners in Rosedale, performing at a birthday party for their parents, and finding backers for his one man show. Photo by Sandy Nicholson

As a major part of their training they are each paired with one artistic member (usually a Soulpepper founding member) and a philanthropic mentor (in most cases a wealthy business couple) by Albert Schultz, the Artistic Director of Soulpepper. The Academy members are required to forge a relationship with the philanthropic mentors they are paired with. This includes talking to them at functions, wine and cheese at pre-openings, dinners together, and sitting with them on opening night –at least once a month, but potentially three or four times a month.

“It was our responsibility to forge a relationship with these people, as it was theirs as well,” says Mike Ross, a graduate of the Soulpepper Academy and a current Associate Artist at Soulpepper. “We were expected to spend time with them. It was actually something that was a little intimidating at first because, although everybody’s there for the same reason, it’s different kinds of people – the artists and often time business-world people. It’s not easy to walk up to someone like that cold and start getting to know them.”

After two years, though, they get over this awkwardness. For Mike Ross, he became friends with his mentors – David and Robin Young of the Young Centre. “We’ve developed enough of a relationship that Soulpepper this season is producing a one man show of mine that they’re the private sponsors for specifically,” he says. “It became a surprisingly casual relationship.”

“I would be very nervous, if it wasn’t for my experience here, going up to what, at that point, I would have deemed just a rich person and asking them for money. I don’t feel that’s the case anymore – I’m asking them to create a relationship, which is a different thing. That’s for them something we can share in. It’s not just handing your chequebook over and maybe giving a shout out on opening night. We’re going to be part of something all together and all get something out of it.”

Soulpepper is thriving. With only 10% of their over 8 million dollar a year revenue coming from government funding, they have obviously found a way to create a sustainable theatre company through their network of private donors – without using tax dollars. They have made relationships with these people who have money to donate and made them part of theatre –made them invested in the arts on a monetary, personal and emotional level. They are teaching developing artists the skills to be able to schmooze and develop relationships with donors and learn the art of theatre as a business.

With Soulpepper it works. They produce classical plays that are generally audience-friendly, with well-known Canadian actors and theatre artists. With plays by Tom Stoppard, David Mamet and Edward Albee, starring actors like Eric Peterson straight from his success on Corner Gas, it’s an easier sell to people outside the theatre community than other companies producing new creations.

But can this model work elsewhere? What about those artists who don’t want to produce classical audience-friendly theatre? Would a business-minded couple be interested in supporting political or experimental theatre?

Mike Ross had a great opportunity to be paired with David and Robin Young, who are devoted and involved with the company. But this method of fundraising raises new questions about creative support: What about those Academy members who are paired with less enthusiastic mentors? What if they don’t get along? What would happen to a student who offended a donor? Or does Soulpepper already ensure that won’t happen by choosing artists that certainly wouldn’t offend donors?

Theatre is created when there is the capital available to create it. There is constantly a struggle to reconcile the need to create art that artists believe in, with the need to finance that art. This isn’t a new problem. Finding money for theatre projects and adapting the product to get that funding is a problem that has been around a very long time. Moliere, Stanislavsky and Shakespeare all forged personal relationships with wealthy elites to facilitate their art.

So this certainly isn’t a black and white issue. One one hand it begs the question, “Has Soulpepper taken the model too far for 21st Century sensibilities? Are they influencing young artists to focus on the sell-ability of their creations over developing new riskier works? It would be simplistic to stop there however, considering the other two major resources for creating theatre: grants and ticket sales. The sad state of arts funding for independent artists in Canada combined with recession-era entertainment budgets leaves few alternatives. Perhaps creating art is living with a series of compromises.

* Data courtesy of theatres and/or the charitable section of the CRA website.

You can read more articles by Lindsay on her own website, Toronto Theatre Thoughts.

Recent Comments