Masks, Morphing and Motion

Balinese topeng masks (photo: Gunawan Kartapranata)

As far as we’re aware, Faster than Night is one of the first handful of theatre productions in the world to use facial performance capture live on stage. But while from one perspective it is cutting-edge technology, it is also just the latest mutation of an artform that has been used in theatre for millennia: the mask.

A mask is simply non-living material sculpted into the shape of a face. It can allow a human performer to transform into a different human, or an animal, or a supernatural being.

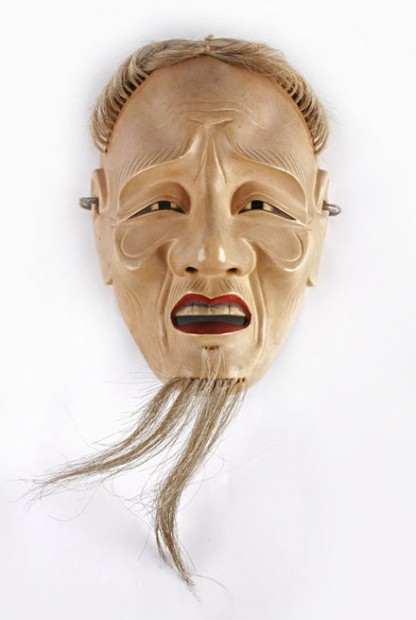

“Ko-jo” (old man) Noh theatre mask (Children’s Museum of Indianapolis)

It can allow a young person to play an old person, or a man to play a woman.

It can define a character by a single facial expression (0r if the mask-maker is very skilled, several expressions depending on the viewing angle).

In the Balinese tradition of topeng pajegan, a single dancer portrays a succession of masked characters with different personalities: the old man, the king, the messenger, the warrior, the villager. A whole epic story can be told by one skilled performer, simply by switching masks and physicalities.

Just as animation is a series of still drawings, or film is a series of still photos projected fast enough to create the illusion of movement, real-time facial capture is fundamentally a process of switching and morphing between dozens of digital “masks” – at rates of up to 120 frames per second.

But how does real-time facial capture actually work?

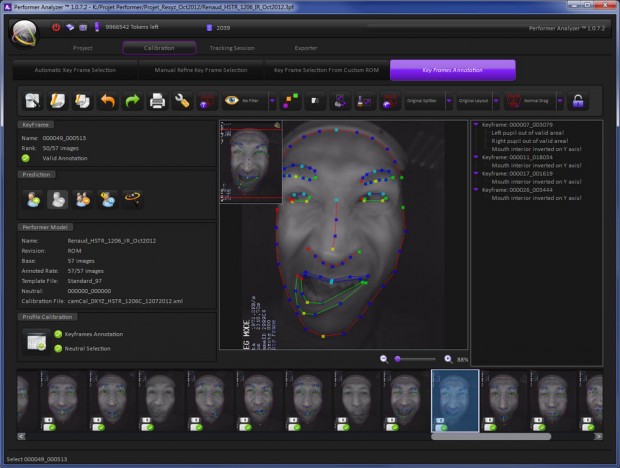

We’re working with the Dynamixyz Performer suite of software, which takes live video from a head-mounted camera, and analyzes the video frames of the actor’s face. In the image below, you can see it tracking elements such as eyes, eyebrows and lips.

For each frame of video, the software finds the closest match between the expression on the live actor’s face, and a keyframe in a pre-recorded library of that actor’s expressions, called a “range of motion”. That library keyframe of the actor corresponds to another keyframe (also called a blendshape) of the 3D CGI character making the same expression. By analyzing these similarities, the software can “retarget” the performance frame by frame from live actor to virtual character, morphing between blendshapes in seamless motion. This process is called morph target animation.

Here are a few rough first-draft keyframes for Faster than Night. On the right is a head-cam video frame of Pascal Langdale, and on the left is an animation keyframe by Lino Stephen of Centaur Digital:

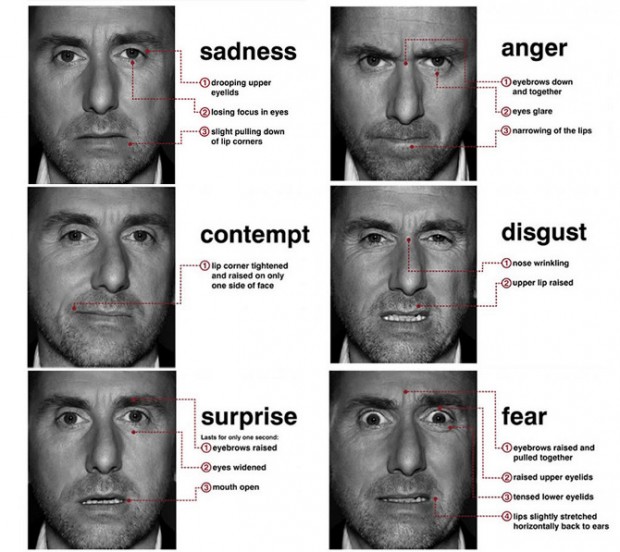

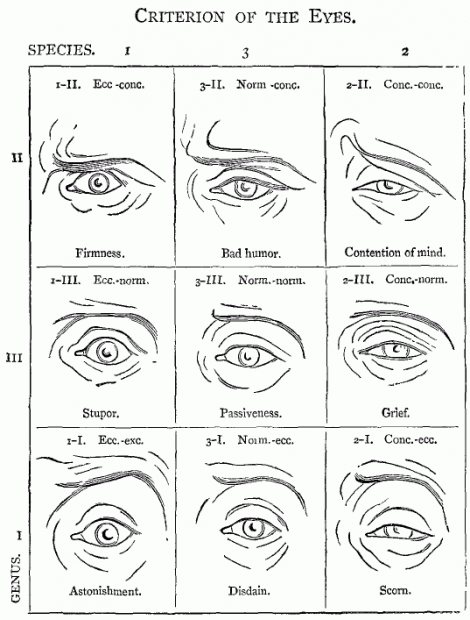

There are dozens more expressions in the “range of motion” library for this particular actor / character pair. Some of them are “fundamental expressions”, drawing on the Facial Action Coding System developed by behavioural psychologists Paul Ekman and Wallace V. Friesen in 1978:

Tim Roth played a character inspired by Paul Ekman in the 2009 TV series Lie To Me

Other facial “poses” convey more subtle or secondary expressions…

…while still other expressions represent phonemes, the building blocks of lip-sync, as found in traditional animation:

Disney animator Preston Blair (1948)

This image of Aardman Animation’s stop-motion character Morph gives a tangible metaphor for what’s going on inside the computer during the real-time animation process:

With each frame, a new head is taken out of its box and put on the character, just like the topeng performer switching masks.

The cumulative effect creates the illusion of speech, of motion, of emotion… of life:

Recent Comments