Why _____ B? – Notes on Context

by Francisco Fernando Granados

The The Ballad of _____ B is site specific performance for the stage that will be presented as part of HATCH 2014 at the Harbourfront Centre Studio Theatre on April 26th. The piece brings into focus a 2-year-long exploration of the ways in which migrant bodies, particularly refugees, are compelled to tell their stories. The idea for the piece came after a friend of mine who teaches ESL brought to my attention a passage from a vocabulary lesson found in the ‘Canadian Mosaic’ unit of a workbook for one of the classes they were teaching.

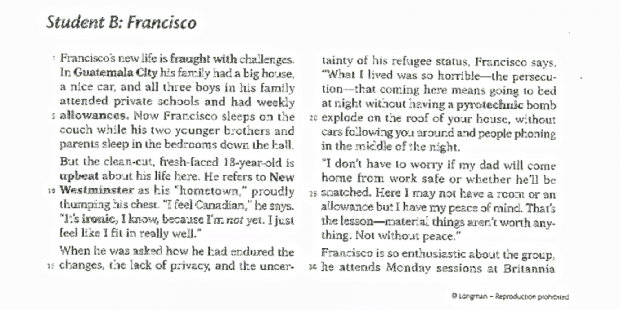

I was ‘Student B’ 11 years ago. The text was lifted word by word, without my knowledge or consent, from a 2003 article in the Vancouver Sun titled Climbing Mount Canada. In the aftermath of 9-11, at a time when most headlines about racialized newcomer youth focused on crime and school dropout rates, the article interviewed four immigrant and refugee teenagers, myself included, about our volunteer work for a publicly funded community peer support program in the Greater Vancouver area.

It was a standard story that set up the brutal experiences that had brought us to this country as the background for a celebratory tale of multicultural Canadian benevolence. The appropriated textbook version of the article included the stories of two other youth: Student A and Student C. One of them, Student C, is still a very close friend of mine.

For The Ballad of _____ B, I am only working with my narrative. I have left my peers’ names and stories out of the project as a matter of respect, but in terms of providing some context for the piece, it is important to mention that the three of us were part of a larger movement in BC in the early 2000’s that sought to give visibility to issues of racial discrimination, barriers to education, and the early stages of the harsh immigration policies that continue to affect the lives of immigrant and refugee young people in this country today.

Attempting to reflect critically on these issues as our stories began to be represented in the media led us to want to be more that just interview subjects. A group of us began to work with newcomer settlement agencies like the Immigrant Services Society of BC to create models of engagement for other young people like us that provided a similar opportunity to legitimize their skills and aspire to become something beyond the stereotypes commonly associated with racialized first generation migrants.

These collective efforts over the past 12 years have lead to a wide range of community projects including Redefining Canadian, a participatory action research project lead by filmmaker and scholar Joah Lui, where migrant youth learned to make videos and documentaries; the NuYu Popular Theatre Project, which offers free theatrical training based on Augusto Boal’s Theatre of the Oppressed methodology; and the Make It Count campaign, a BC-wide appeal to the provincial government to recognize and accredit migrant students’ language learning towards their high school graduation credits.

I was actively involved in these community efforts first as a participant, then as a coordinator and administrator until around 2009. By then, I was BFA student, had become a Canadian citizen, and felt exhausted and frustrated with the politics of both not-for-profit organizations and community activism. I also became aware of the importance of making space in leadership positions within these movements for the generation of young people who came after early 2000’s batch I belonged to. I decided to focus on finishing my art education and became a professional artist.

My work as a visual artist, primarily in performance, had up until this project rejected narrative structures; this is perhaps due to my disappointment with the ways in which migrant narratives are often de-contextualized and appropriated by governments, non-profit groups, and activists that seek to represent those whose voices cannot be listened to within the current structures of the political economy. But the surprise of the encounter with my own story in the form of a language lesson, reaching from the past, compelled me to engage with narrative as a form.

After a couple of years of holding on to the text without knowing exactly what to do with it, I realized that engaging with narrative required two aesthetic moves: spacing and redistribution. As a man in my late 20’s, making a living as a sessional instructor in an art school in Toronto, it was hard for me to identify with the figure of the student. I am relatively young, but I am a teacher these days. My primary training in drawing has left me with a voracious curiosity for linear structures. In reclaiming this particular narrative, I wanted to create spaces within the text that would allow for something to happen. Line became the instrument of spacing. Thus Student B became _____ B.

The second move was re-distribution. I will write about this next week.

[…] contributions of the public will be a way to bring together the previously discussed tactics of spacing and redistributing of the elements of […]